Can’t keep up the full-blown posts while school’s in session. This isn’t everything seen, heard, and read this semester — just what I can remember off the top of my head.

Can’t keep up the full-blown posts while school’s in session. This isn’t everything seen, heard, and read this semester — just what I can remember off the top of my head.

Atonement, Ian McEwan (2001). Hundreds of terrific sentences and a lively yarn. Is it now always necessary that every novel has to be about both what it’s about and also about novelists?

Ex Machina, Alex Garland (2015). This made me so mad but now I’m having trouble even remembering it. I think it had to do with the fact that it was masquerading as being all Jaron Lanier philosophical when really it’s just about grubby horny boys wanting to look at sexy naked girls without feeling bad about it. Two choices available to female-coded beings in this world: slave or murderer. See my commentary elsewhere regarding those recent Scarlett Johansson movies; she’s the queen of this kingdom, and Luc Besson is its Don King.

Believing Is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography, Errol Morris (2011). Manic, obsessive, repetitive, and great investigation of photography’s truthiness and its consequences. Particularly astute on the ways photographs can be put to use as political propaganda.

Diogenes the Cynic: Sayings and Anecdotes, With Other Popular Moralists, ed. Robin Hard (2012). I didn’t like Diogenes as much as I thought I would. His inconsistencies irritate me. Turns out I’m more of a Seneca guy. What are you going to do.

Dialogues and Essays, Seneca. Still working on this. Not as immediately accessible as Marcus Aurelius but I’m warming to it.

Meditations, Marcus Aurelius. I love this like I love Montaigne; their spirits are so close. (My understanding is that Montaigne oddly doesn’t seem to have known Aurelius — a pity.) The Staniforth translation is the best. The Robin Hard one may be “better” for classicists but it’s awful for human consumption.

Welcome to Me, Shira Piven (2014). A little Truman Show, a little Nurse Betty, a little To Die For. Doesn’t quite hold together, is too one-note and too relentlessly committed to despair, but it’s still a smart movie.

Father Comes Home From the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3), Suzan-Lori Parks (2015). If you’re struggling to write a play about a soldier come home from a war and you find out that your favorite living playwright’s new play is titled “Father Comes Home from the Wars,” you have some kind of mixed feelings. But the main feeling here is satisfaction, since this is one of Parks’ best. I admire her so much. I’m particularly impressed that she’s getting less and less obscure, but isn’t losing any of the fundamental ambivalences that make her work so provocative. This work is every bit as incisive and destabilizing as, say, The America Play, but I can also imagine this one put on by a high school drama club, whereas earlier work was a bit too far out for that kind of venue. Wonderful, wonderful piece; wish I could have seen it at the Public.

The Sellout, Paul Beatty (2015). Beatty reminds me of my good friend Jeffrey McDaniel, such a fecund imagination that he’ll never use one clever metaphor when three have come to mind. The novel works as a crazy comic satire on contemporary race relations, politics, poverty, capitalism, Los Angeles, and also as a sort of fictional beard for Beatty’s more essayistic commentaries on all of the above. I sometimes wish Beatty didn’t feel the need to stuff every single sentence with as many jokes as possible, but all that candy is laced with enough acid that I suppose it balances out in the end.

Also reread Roth’s The Radetzky March and The Emperor’s Tomb this fall, for fun.

Also reading more Simon Stephens plays.

TV: Sandy convinced me to watch Orphan Black. It’s pretty dumb but I did watch the whole thing. It’s kind of ironic that here you have a show with all these strong female characters, but only one actress getting work! Also watched the Netflix series Narcos, FX’s The Americans, and Amazon’s The Man in the High Castle. Also re-watched the entire span of The Wire and thought it’s holding up very well. More and more, I find I watch fewer movies and more series. This depresses me a little, but I don’t know why.

Listening: Nicholas Jaar, Claude von Stroke, The Juan Maclean, Dexter Gordon, McCoy Tyner, Maya Jane Coles. Utterly in love with my absurdly expensive Spotify subscription.

Looking: Thinking a lot about August Sander’s People of the 20th Century, Sternfeld’s Stranger Passing, and this post from Blake Andrews on “docutrinity.”

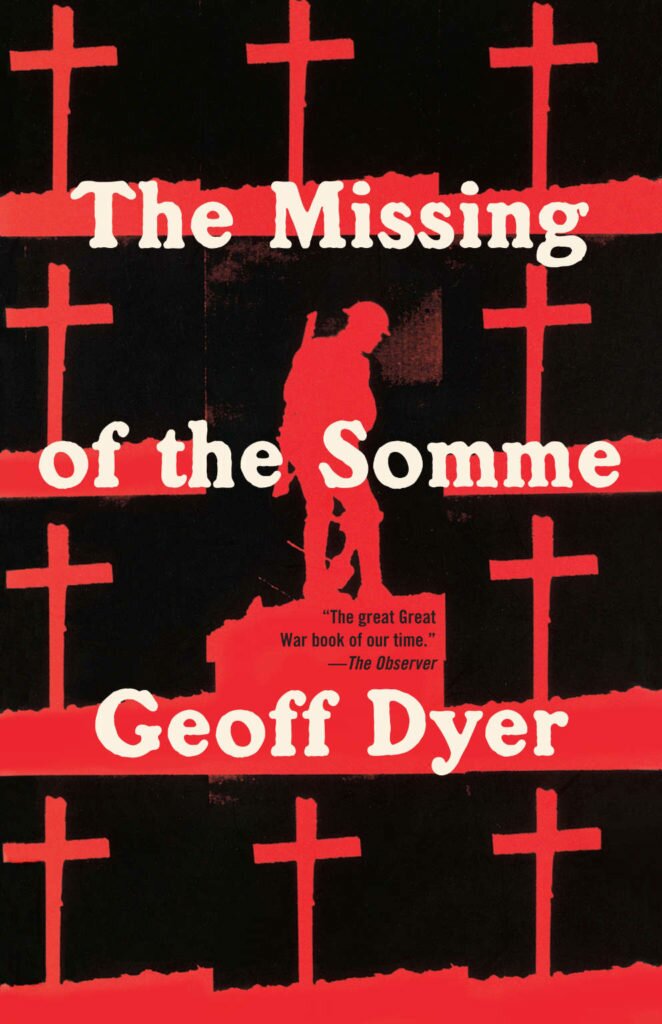

Dyer’s book is about trench warfare, World War I, artistic responses to war (especially in literature), the conventions of war memorial sculptures, his personal journeys around WWI battlefields and cemeteries in France, and other things, but his main concern is the nature of cultural memory. How do societies construct and revise the past? “The issue, in short, is not simply the way the war generates memory but the way memory has determined — and continues to determine — the meaning of the war.”

Dyer’s book is about trench warfare, World War I, artistic responses to war (especially in literature), the conventions of war memorial sculptures, his personal journeys around WWI battlefields and cemeteries in France, and other things, but his main concern is the nature of cultural memory. How do societies construct and revise the past? “The issue, in short, is not simply the way the war generates memory but the way memory has determined — and continues to determine — the meaning of the war.” 600 Miles, Gabriel Ripstein (2015). You can’t just point a camera at someone driving a car with golden hour light on their face and let it run for three minutes. It’s not suspenseful; it’s boring. A small story like this depends on effective characterization and unfortunately that doesn’t happen here. Too bad because we have a dire need to see normal human Mexicans on the screen instead of just caricatures and thugs.

600 Miles, Gabriel Ripstein (2015). You can’t just point a camera at someone driving a car with golden hour light on their face and let it run for three minutes. It’s not suspenseful; it’s boring. A small story like this depends on effective characterization and unfortunately that doesn’t happen here. Too bad because we have a dire need to see normal human Mexicans on the screen instead of just caricatures and thugs. I stumbled across this and it sounded in theory like something I’d be very interested in: a novel about a soldier coming back from Iraq with undiagnosed PTSD (a subject I’ve been researching and reading about for years now as I struggle with my own work on a similar subject), and even better, the solider is a woman (as is the author, obviously), and that’s a demographic that’s badly underrepresented in literature. In my “Uses of History” class, during the unit on war’s continuing effects on returned soldiers, I always teach Sigrid Nunez’s great For Rouenna; it’s one of the very few novels I know of that takes up the lingering effects of war on women who’ve served. Even more, reviews of Hoffman’s novel promised that she also incorporated the realities of class in Be Safe I Love You; the returned soldier, Lauren Clay, enlisted out of a sense of economic responsibility to her family. This too is an aspect too often missing from contemporary war literature and film. I’ve looked at a lot of novels, stories, plays, journalism, documentary films, and fictional films about soldiers coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan; not many focus on veterans’ economic realities.

I stumbled across this and it sounded in theory like something I’d be very interested in: a novel about a soldier coming back from Iraq with undiagnosed PTSD (a subject I’ve been researching and reading about for years now as I struggle with my own work on a similar subject), and even better, the solider is a woman (as is the author, obviously), and that’s a demographic that’s badly underrepresented in literature. In my “Uses of History” class, during the unit on war’s continuing effects on returned soldiers, I always teach Sigrid Nunez’s great For Rouenna; it’s one of the very few novels I know of that takes up the lingering effects of war on women who’ve served. Even more, reviews of Hoffman’s novel promised that she also incorporated the realities of class in Be Safe I Love You; the returned soldier, Lauren Clay, enlisted out of a sense of economic responsibility to her family. This too is an aspect too often missing from contemporary war literature and film. I’ve looked at a lot of novels, stories, plays, journalism, documentary films, and fictional films about soldiers coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan; not many focus on veterans’ economic realities.