I’ve been ambivalent about Sally Mann’s work for a long time — to put it kindly — and probably wouldn’t have read this if Wendy hadn’t gotten it for me for Christmas, but I’m really glad she did because I really enjoyed it. This is not to say that I’m any more enthusiastic about the work than I was, though. In fact, I’m probably less interested in the art than I was before, which was not much, but I’m a lot more interested in the artist.

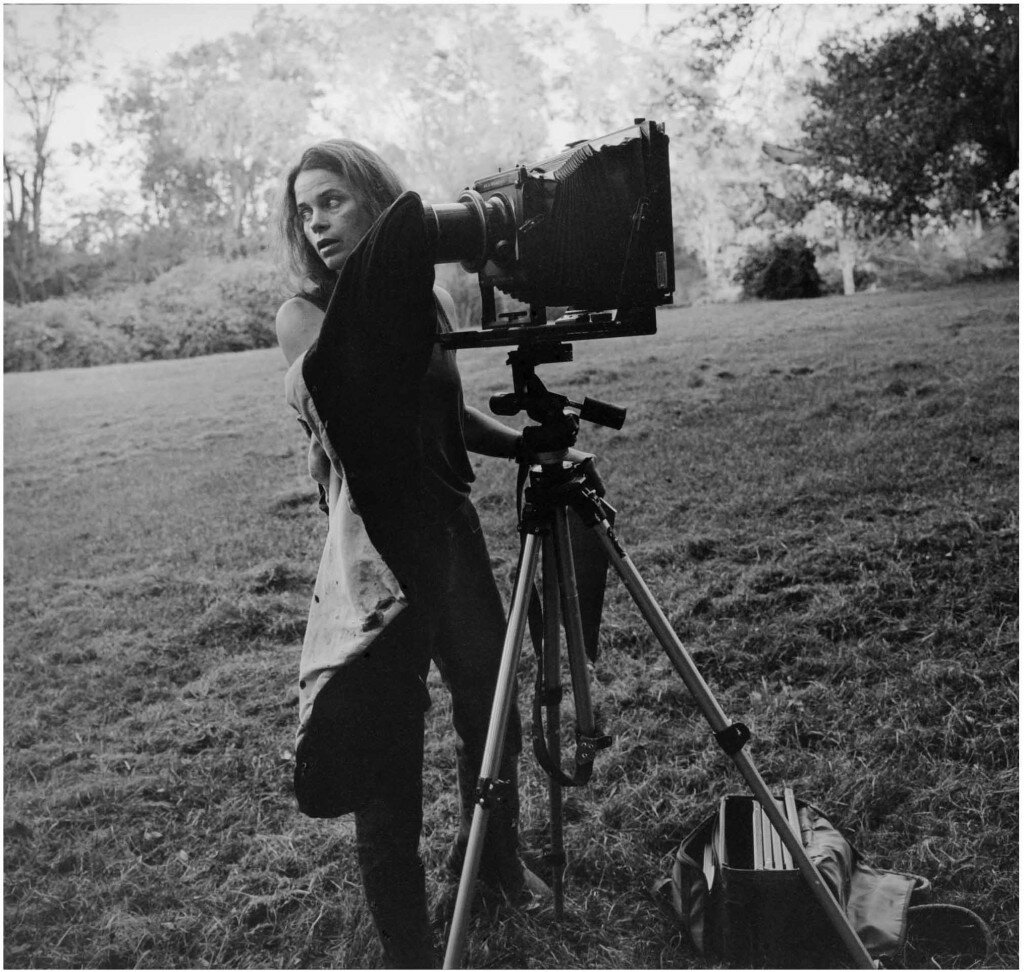

I never had trouble with Mann for the reasons others did; the idea that she’s a child pornographer is ludicrous. I always thought she was more of a class pornographer, race pornographer, and history pornographer. The feral children eating homegrown food from roughhewn bowls and playing in the mud by the river seem to argue for the beauty and purity of an Appalachian noble savage existence, but always reminded me that those must be some pretty rich white kids to be getting their picture took with an 8×10 view camera, and that a lot of Appalachian kids are running around with no clothes not because of their parents’ theories on parenting but because they don’t have any fucking clothes.

Mann marches right into The Help territory in her memoir when it comes to her point of view on her race privilege:

“Down here, you can’t throw a dead cat without hitting an older, well-off white person raised by a black woman, and every damn one of them will earnestly insist that a reciprocal and equal form of love was exchanged between them … Cat-whacked and earnest, I am one of those who insist that such a relationship existed for me. I loved Gee-Gee the way other people love their parents, and no matter how many historical demons stalked that relationship, I know that Gee-Gee loved me back.”

It’s interesting, I think, how her diction gets all gee-whiz vernacular and her syntax turns baroque here; it’s almost like she’s trying to not quite say what she’s saying. Further, almost funny, certainly sad, is Mann’s description of her current project, which consists of hiring black men as models and then taking their pictures. Such a project seems unlikely to cause Mann or anyone else to learn much new about power dynamics between blacks and whites. Now, if she paid black photographers to take her picture, that I might be interested in.

Then there’s history. I’m sorry, I know this is an insane thing to say, but anyone that makes a picture of anything with wet-plate collodion process, especially south of the Mason Dixon line, is playing on the viewer’s deep, semi- or unconscious attraction to nostalgia and historical amnesia. Any contemporary collodion photograph, in addition to whatever else it is saying, also says, “Don’t you long for the old days, when things were simpler and everyone knew their place?” Everything that Eggleston did to prove that the South exists in Kodachrome color, and contains automobiles and swimming pools and freeways, can be undone or at least undermined by a single sepia Mann landscape of a mournful live oak in its misty shrouds of Spanish moss.

So I don’t seem to be such a Mann fan; why did I enjoy the book? I had no idea what a character she is! And it’s a lot of fun finding out. I’m almost sure I’d find her immensely irritating close up — she’s self-absorbed, histrionic, and touchy, the kind of person who would cause you pain and find a way to make it your fault rather than hers — but she’s fascinating to observe from a distance. Smart as hell, full of feeling, with deep gusto for a good story, and such a huge and powerful sense of ambition that I can’t help but feel awed by it. No matter how you feel about the pictures, you’ll find this an irresistibly weird and engaging memoir.