A complete but very decadent and perhaps somewhat transgressive delight, based on the real-life story of August Engelhardt, a German nudist vegetarian who decamped for the south seas to start a utopian colony at the fin de siècle. I came across this by accident and really enjoyed it, not least, admittedly, because I realized that I went to college with Kracht and I had no idea he’d gone on to write novels. What a hoot! Kracht’s got a wonderfully arch and acerbic comic style and skewers placid colonial burghers and idealistic nuts (ha) like Engelhardt with equal verve.

A complete but very decadent and perhaps somewhat transgressive delight, based on the real-life story of August Engelhardt, a German nudist vegetarian who decamped for the south seas to start a utopian colony at the fin de siècle. I came across this by accident and really enjoyed it, not least, admittedly, because I realized that I went to college with Kracht and I had no idea he’d gone on to write novels. What a hoot! Kracht’s got a wonderfully arch and acerbic comic style and skewers placid colonial burghers and idealistic nuts (ha) like Engelhardt with equal verve.

All posts tagged “novels”

The Foundation Trilogy, Isaac Asimov (1951-1953)

This semester I’m teaching a class called “The Uses of History,” where students read works of literature that in some way are informed by specific historical events, and produce such texts themselves. (The secret of the class is that there aren’t any works of literature that aren’t informed by specific historical events. This secret generally becomes an open secret around week two or three, if all goes according to plan.)

This semester I’m teaching a class called “The Uses of History,” where students read works of literature that in some way are informed by specific historical events, and produce such texts themselves. (The secret of the class is that there aren’t any works of literature that aren’t informed by specific historical events. This secret generally becomes an open secret around week two or three, if all goes according to plan.)

When I teach this class, I find I think surprisingly often of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy. I first came across the Foundation Trilogy when I was, I think, in junior high or maybe high school, and I found it the same way I found most everything I read before I left home from college, by picking through my father’s inexhaustible book shelves. Most of those books came from a book distribution warehouse where my father worked summers as a college student. Unsold books were sent back to the warehouse and their covers were torn off so they couldn’t be resold. I’ve never really understood how the system was supposed to work, but I guess the basic idea was that it was easier and more economical to render the books unsellable than it was to ship them back to wherever they’d come from. So most of my father’s library consisted of coverless classic paperbacks, from Augustine to Xenophon. But I remember that the Asimov had a cover. My dad must have paid for that one.

When I think of The Foundation Trilogy, it’s usually because of the narrative and thematic significance of a single character, known as “the Mule.” In the novels, a great galactic empire comprising thousands of worlds and billions of people is slowly collapsing. A team of talented social scientists known as “psycho-historians,” led by a man named Hari Seldon, can see this end coming, and can mathematically predict that millennia of bedlam, ignorance, and despair will follow it. Through unfathomably sophisticated sociological calculations, they devise a plan – the Seldon Plan – which will limit this dark age to a mere handful of centuries, after which a fresh civilization – the Second Empire – will rise. Asimov’s is an Enlightened technocratic fantasy of the purest type. The Seldon Plan represents the idea that science and rationality can – will! must!– solve the problems of chaos and pain. The drama of the novels resides in the unfolding of the Seldon Plan, and the frequent threats to its success. The greatest of these threats is the appearance of the Mule.

The Mule doesn’t look like much. When we first meet him, he’s presented as a disfigured and simpering clown. But he has a slight mutation which enables him to subtly bend the mental processes of others, and this capability permits him to conquer worlds, amass a great deal of power, and build casinos. (OK, the “build casinos” part was a joke, but it should be noted that the Mule chooses Kalgan, a vacationer’s planet with a strong resemblance to Atlantic City, as his capital.) Now to be sure, a petty warlord taking over a few planets is generally no big deal; such contingencies are well within the capacious and complex calculations of the Seldon Plan. But the psycho-historians soon come to realize, to their horror, that the Plan has not factored in the kind of mutant disruption the Mule represents. His appearance was wholly unpredictable and unpredicted, and the entire Plan is thus at risk of unraveling.

We humans have a compulsive habit of trying to impose narrative coherence on sequences of historical events, but such rationalizations, as the historiographer Hayden White has argued with such eloquence, are untrustworthy at best, and dangerously seductive at worst. They are inevitably influenced by (or even determined by) underlying ideological or moral assumptions and values, and are engineered to reassure us that the progress of history is orderly and tends toward coherence. It’s common, for example, for people to say that the Allies defeated the Axis powers in World War II because in the end, good must triumph over evil. Or that the Roman Empire fell because its people became lazy, decadent, and complacent. Those are satisfying stories. But history isn’t a story. The Mule represents for me, and reminds me, that any narrativization of history (or rationalization, or Seldonization, if you like), is always imminently and immanently subject to a jolt of the unpredictable, irrational, or perverse. This is such an important reminder that the character of the Mule has become a rather important totem for me, despite the fact that I haven’t read these books since I was a kid.

Last month I decided to finally re-read the novels, and I’m glad to report that The Foundation Trilogy has held up wonderfully both as an entertainment and as a fertile ground for historiographical musings. I highly recommend it. Remember, though, that it is itself a story, not a history. Don’t let the fate Asimov assigns the Mule lead you into intellectual temptation. The good guys aren’t necessarily fated to win. The most intelligent and rational choices don’t always prevail. Against all reason, people are very frequently willing, even eager, to act against all reason. “The fully enlightened earth radiates disaster triumphant.” Adorno and Horkheimer. My favorite Modernist catch-22. The better we get at rationalism, the better we get at madness.

On election night, Wendy had a bunch of women over to the house to watch the returns. Several of them brought their daughters. Someone made cookies with Hillary Clinton’s campaign logo embossed in frosting on them. The scene in the living room was noisy and chaotic, and I went upstairs to read the last few chapters of The Foundation Trilogy in my room, thinking I’d come down around the time polls closed in the Midwest, to share the champagne and – I was really looking forward to this, more than I’d even admitted to myself – to watch those mothers be with their daughters and those daughters be with their mothers. Instead, the Mule. I’m only surprised that I was surprised.

The Loser, Thomas Bernhard (1983)

I am not usually given to artist-groupie activities. I spent a year in Paris and felt no need to seek out Baudelaire’s grave; I took the tour of Emily Dickinson’s house in Amherst and found it nearly as boring as church. But when I went to Vienna some years ago, I did visit the Bräunerhof cafe frequented by Thomas Bernhard, and I did sit there for an hour with a coffee and Linzer torte, thinking about him, and about the European culture that made him possible and disgusted him for having done so. There was a time when I would have called him my favorite writer.

I am not usually given to artist-groupie activities. I spent a year in Paris and felt no need to seek out Baudelaire’s grave; I took the tour of Emily Dickinson’s house in Amherst and found it nearly as boring as church. But when I went to Vienna some years ago, I did visit the Bräunerhof cafe frequented by Thomas Bernhard, and I did sit there for an hour with a coffee and Linzer torte, thinking about him, and about the European culture that made him possible and disgusted him for having done so. There was a time when I would have called him my favorite writer.

I read The Loser once before, a long time ago, but all the recent news from Europe made me curious to look back into him, or through him. I can’t quite say why. He functioned for me, in my yoot, as an emblem of of a type of European-ness, unfathomably cultured and decadently cynical, or the other way around, which I both envied and deplored. (Like almost all young people, I was ignorant of history and scattershot in my education; only years later would I discover Robert Musil, and realize that Bernhard hadn’t come from nowhere, as I’d imagined.) Since I last read The Loser, the Berlin Wall has fallen, the Eurozone came into being, and a Moroccan-born Muslim was appointed mayor of Rotterdam. My imaginary Europe has changed. The experiment was to re-read The Loser while thinking about Syria.

It was either a useless experiment or one whose value has yet to reveal itself. Bernhard’s masochistic attack on mediocrity (his own, and everyone else’s) is even more relentless and tuneless than I remembered. I once found the relentlessness exciting and the tunelessness edifying; this month the book’s seemed to me absurd and dull. I can feel that it’s too soon to be writing this note, that my thoughts haven’t jelled, but I’m doing it anyway, because I want to be done with it.

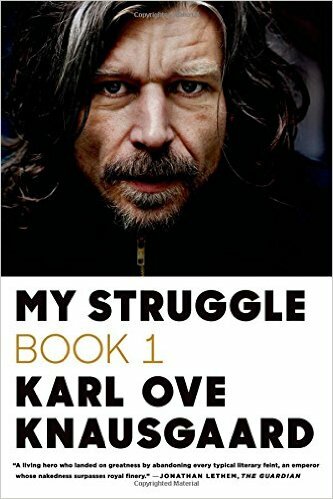

My Struggle: Book 1, Karl Ove Knausgaard (2009)

“How important can it be that I suffer and think? My presence in this world will disturb a few tranquil lives and will unsettle the unconscious and pleasant naiveté of others. Although I feel that my tragedy is the greatest in history—greater than the fall of empires—I am nevertheless aware of my total insignificance. I am absolutely persuaded that I am nothing in this universe; yet I feel that mine is the only real existence.” — E. M. Cioran, On the Heights of Despair

“How important can it be that I suffer and think? My presence in this world will disturb a few tranquil lives and will unsettle the unconscious and pleasant naiveté of others. Although I feel that my tragedy is the greatest in history—greater than the fall of empires—I am nevertheless aware of my total insignificance. I am absolutely persuaded that I am nothing in this universe; yet I feel that mine is the only real existence.” — E. M. Cioran, On the Heights of Despair

I was wary about this enormous Knausgaard thing when everyone started talking about it, as I’m always wary when everyone starts talking about something, but then I read this article, which I thought was really beautifully written, and I thought, yes, I need to give the book a try. I’m giving up after about 250 pages, which means I’ve read only 7% or so of Min Kamp‘s total tonnage. I’ve read the reviews about the book’s genius lying in its relentless commitment to evacuating artifice from the recounting of experience; I am called upon to appreciate its indifference to being appreciated. This seems to me a rather monumental example of the imitative fallacy, and I don’t think I’ll need to read 3,600 pages of it in order to understand that, any more than I need to take an hour to admire the brush strokes on a Warhol soup can canvas. Like Kenneth Goldsmith’s Day, the Knaussgard book makes me feel like if I were actually to read it, I’d be some kind of sucker. Goldsmith professed his intention to “cleanse myself of all creativity” through the writing of Day; Knausgaard ends the six-volume My Struggle with a similar sentiment: “I am happy because I am no longer an author.”

Was he ever? If My Struggle is not just a conceptual work to be regarded rather than actually read, if it really is a novel written by an author to be read and experienced as art, then it is awful. I’m reminded of the ways that Boyhood bored and annoyed me. Like Cioran says, every ordinary human’s struggle seems imponderably significant to herself or himself. That’s natural enough. But to assert that struggle is relevant to others is adolescent narcissism, nothing more. I here expose myself to the charge that no life is ordinary, that we all of us contain inexhaustible galaxies of thoughts, sensations, ambitions, impressions, emotions, opinions, disappointments, passions. Fair enough, and a lovely thought. I suppose it follows then that being trapped with any random human in an elevator for a month would be an inexhaustibly fascinating experience. Enjoy that. I’ll take the stairs.

And finally: There is something very male about both this book and its reception. It seems to me undeniable that My Struggle‘s success would have been impossible if it were not drawing on the mythic notion of the heroic male novelist. In other words, if a woman had tried to do something like this, no one would have paid a lick of attention to it, or if they did, they would be much quicker to call it what it is: monumentally narcissistic and dull.

The Flamethrowers, Rachel Kushner (2013)

Many contemporary American novelists write novels to mansplain contemporary America to me which is one reason I tend not to read many contemporary American novels. Rachel Kushner starts racking up points with me from page one on the basis of her chosen subjects and settings alone; I cannot recall ever having read a novel set in the New York art world of the 1970s, industrializing northern Italy in the 1950s, or leftist Italian movements of the 1970s, much less all three.

Many contemporary American novelists write novels to mansplain contemporary America to me which is one reason I tend not to read many contemporary American novels. Rachel Kushner starts racking up points with me from page one on the basis of her chosen subjects and settings alone; I cannot recall ever having read a novel set in the New York art world of the 1970s, industrializing northern Italy in the 1950s, or leftist Italian movements of the 1970s, much less all three.

The novel opens with our protagonist, Reno, a young would-be artist, using a fancy Italian motorcycle to make a mark on the Bonneville Salt Flats. Everyone else present is there to marvel at the power and force of machinery; Reno is there to make a drawing of impermanence. The novel ends (don’t worry; only the mildest of spoilers to follow) with an Italian would-be anarchist using a set of borrowed skis to make a mark on the side of Mont Blanc as he flees the police pursuing him for crimes he’s committed against the Italian industrialist family who manufactured the fancy Italian motorcycle aforementioned. You begin to see the layers of theme and association Kushner’s built up. The novel is about the rise of industrialized postwar capitalism, its early roots in Futurist fetishization of machinated speed, the ways in which its apparent hegemony was undermined by anarchic movements artistic and political, and the ways in which those movements began to fail.

At what point did modernity start to seem other than purely glorious? Everyone’s got a different answer for that, depending on where and when you come from. 1914, 1945, 1967 — you can make strong arguments for any of these, of course. You don’t hear hear 1978 very often, the year the Red Brigades killed Aldo Moro. Have kids these days ever heard of Aldo Moro, or Baader-Meinhof? There’s probably a band in Bushwick named Red Army Faction. God, that’s a depressing thought.

Anyway, apparently Kushner (b. 1968) is old enough to know and young enough to be able to reimagine those “years of lead” when the ideologies of the 1960s turned into the uprisings of the 1970s, and then everything went to hell.

I’m going on about politics because that’s the part most interesting to me, but Kushner’s evocation of the New York art world at this moment is actually the most entertaining part of the book. The implicit but never enforced idea is that the revolutionary movements in art going on at the same time as these attempts at political revolution and anarchism are just as exciting but finally just as overheated, under-baked, and doomed to be remembered more as zigs and zags of fashion than agents of actual upheaval. The characters Kushner creates in the Soho of the early 1970s are wonderful, and it’s fun too to guess who’s supposed to be representing actual artists of the time; I think I may have spotted William Eggleston? Can that be right?

There’s some unevenness in this book — some scenes can feel like they were only written because Kushner had to get someone from point A to point B — but there are some sequences that are genuinely thrilling in their cascades of association which seem both truly surprising and absolutely inevitable. It’s not a perfect novel, but it’s the best work of contemporary fiction I’ve read in a long time.

I’ve got one other line of thinking that doesn’t make me very happy. Our protagonist Reno is a young woman from nowhere (Reno) trying to navigate all the sophistication and sophistry of the rich, the urban, the Italian, the artistic, etc. I wish she had in the end, or even the middle, found something to be other than a girl who looks to men to define her, and something to do other than react to situations. She begins the book with an idea about an art project; Kushner doesn’t let her do anything with it, and by the end, we’ve pretty much forgotten that she ever had any artistic ambitions at all. Is that supposed to be a comment on the fate of female artists of the time? That seems like an interpretive stretch. Anyway, I’m just saying that I felt more interested in Reno’s artistic aspirations than she seemed to be herself.

The Orphan Master’s Son, Adam Johnson (2012)

A thoroughly enjoyable, tautly written, cleverly plotted novel, and one perhaps more subtle than it seems. Because Johnson’s research on life in North Korea is pretty clearly in place, we buy into the idea that we’re reading realism here. But how do you write realism about a place where reality is perpetually subject to change at the whim of the state? As events in the novel get stranger and stranger, you start doubting the realism that you took for granted at first — Is it really possible that Kim Jong Il commissioned a hand-built ersatz Ford Mustang just to humiliate a visiting U. S. Senator? Are there really villages in the DPRK populated entirely by “zombie laborers” who have been given lobotomies by the state? — and thus Johnson is able, in a small way, to create in his reader’s mind a state of surreality analogous to the one which must pervade life in North Korea, where survival requires you to believe in obvious untruths, and the truth itself is unbelievable.

A thoroughly enjoyable, tautly written, cleverly plotted novel, and one perhaps more subtle than it seems. Because Johnson’s research on life in North Korea is pretty clearly in place, we buy into the idea that we’re reading realism here. But how do you write realism about a place where reality is perpetually subject to change at the whim of the state? As events in the novel get stranger and stranger, you start doubting the realism that you took for granted at first — Is it really possible that Kim Jong Il commissioned a hand-built ersatz Ford Mustang just to humiliate a visiting U. S. Senator? Are there really villages in the DPRK populated entirely by “zombie laborers” who have been given lobotomies by the state? — and thus Johnson is able, in a small way, to create in his reader’s mind a state of surreality analogous to the one which must pervade life in North Korea, where survival requires you to believe in obvious untruths, and the truth itself is unbelievable.

So that’s a nifty formal success, yes, but there’s something discomfiting about the enterprise too. We see kidnappings, torture, coercion, murder, starvation, and much else to denote the plight of North Korea’s citizenry, but the novel, weirdly, also feels like a bit of a romp, with loads of exciting set pieces, comic passages, a star-crossed love story, and in the closing moments a Scooby-Doo-esque foiling of Kim Jong Il that left me tickled as a novel-reader but strangely horrified as a human-being. Digging down to get at the exact nature of my complaint here, I strike a layer of iron, or irony — I think I may be wondering whether there are simply some subjects about which novels should not be written.

The Master of Petersburg, J. M. Coetzee (1994)

Not my favorite of Coetzee and not his best, but a remarkable book, amazing to me not least simply because he manages to accomplish here such a complex braid of the historical, the personal, and the imaginary without losing his head. It’s nervy enough for a novelist to take up Dostoyevsky as a protagonist and presume to present the Master’s interiority. Coetzee goes a good deal further by transposing elements of his own relationship with his son onto Dostoyevsky’s with his. He further presumes to write in manner instantly recognizable as Russian-esque, as if he’s working on a kind of stylistic etude. Scenes oscillate between metaphysical speculation and intense sensory realism; the eternal questions of class, religion, and revolution are constantly in play; a chained dog in an alleyway or a battered white suit in a musty valise become occasions of terror and pity.

Not my favorite of Coetzee and not his best, but a remarkable book, amazing to me not least simply because he manages to accomplish here such a complex braid of the historical, the personal, and the imaginary without losing his head. It’s nervy enough for a novelist to take up Dostoyevsky as a protagonist and presume to present the Master’s interiority. Coetzee goes a good deal further by transposing elements of his own relationship with his son onto Dostoyevsky’s with his. He further presumes to write in manner instantly recognizable as Russian-esque, as if he’s working on a kind of stylistic etude. Scenes oscillate between metaphysical speculation and intense sensory realism; the eternal questions of class, religion, and revolution are constantly in play; a chained dog in an alleyway or a battered white suit in a musty valise become occasions of terror and pity.

Coming to this straight from Pelevin’s Omon Ra, I’ll say a word about sentences. In Pelevin the sentences always seemed to be slipping through my fingers, never quite meaning what they seemed, often seeming to mean something other or more. What a contrast to Coetzee, whose sentences seem built stone by stone, every one a kind of temple with the aura of having always existed. I know such authority is a species of illusion, or worse, but the tiny fascist in me (almost everyone has one) does thrill to it.

Omon Ra, Victor Pelevin (1992)

This is a brilliant and heartbreaking little novel which I first read years ago and enjoyed just as much the second time around. Omon is a postwar Russian kid who dreams of transcending the banality of his circumstances by becoming a cosmonaut. The Soviet state is happy to help him do so, since his desire dovetails perfectly with the state’s desire to project an image of achievement and glory to the world. In the end it turns out all parties have been deluding themselves and each other; transcendence and glory turn out to be induced hallucinations. In the sacred profane tradition of Gogol, the story’s both tragic and comic, naturalistic and fabulous.

This is a brilliant and heartbreaking little novel which I first read years ago and enjoyed just as much the second time around. Omon is a postwar Russian kid who dreams of transcending the banality of his circumstances by becoming a cosmonaut. The Soviet state is happy to help him do so, since his desire dovetails perfectly with the state’s desire to project an image of achievement and glory to the world. In the end it turns out all parties have been deluding themselves and each other; transcendence and glory turn out to be induced hallucinations. In the sacred profane tradition of Gogol, the story’s both tragic and comic, naturalistic and fabulous.

And to extend that last point, from a writerly point of view, I marvel at the way Pelevin segues seamlessly from the realistic to the absurd and back again, so that as a reader, you find yourself in a sort of hall of mirrors, where the unbelievable seems inevitable and the simplest explanation impossible. I wouldn’t know for sure, but it seems a perfect stylistic match for what life must have been like behind the Iron Curtain.

The Phoenix

“They have also another sacred bird called the phoenix which I myself have never seen, except in pictures. Indeed it is a great rarity, even in Egypt, only coming there (according to the accounts of the people of Heliopolis) once in five hundred years, when the old phoenix dies. Its size and appearance, if it is like the pictures, are as follows. The plumage is partly red, partly golden, while the general make and size are almost exactly that of the eagle. They tell a story of what this bird does, which does not seem to me to be credible, that he comes all the way from Arabia, and brings the parent bird, all plastered over with myrrh, to the temple of the Sun, and there buries the body. In order to bring him, they say, he first forms a ball of myrrh as big as he finds that he can carry, then he hollows out the ball, and puts his parent inside, after which he covers over the opening with fresh myrrh, and the ball is then of exactly the same weight as at first. So he brings it to Egypt, plastered over as I have said, and deposits it in the temple of the Sun. Such is the story they tell of the doings of this bird.”

“They have also another sacred bird called the phoenix which I myself have never seen, except in pictures. Indeed it is a great rarity, even in Egypt, only coming there (according to the accounts of the people of Heliopolis) once in five hundred years, when the old phoenix dies. Its size and appearance, if it is like the pictures, are as follows. The plumage is partly red, partly golden, while the general make and size are almost exactly that of the eagle. They tell a story of what this bird does, which does not seem to me to be credible, that he comes all the way from Arabia, and brings the parent bird, all plastered over with myrrh, to the temple of the Sun, and there buries the body. In order to bring him, they say, he first forms a ball of myrrh as big as he finds that he can carry, then he hollows out the ball, and puts his parent inside, after which he covers over the opening with fresh myrrh, and the ball is then of exactly the same weight as at first. So he brings it to Egypt, plastered over as I have said, and deposits it in the temple of the Sun. Such is the story they tell of the doings of this bird.”

Herodotus, people.

I haven’t kept up with the blog in about a year. I’ve been in mourning for a failed writing project and obsessed with photography. Like a beaten dog slinking back into the yard, I am slowly returning to the written word, and I resolve to keep up with my reading, viewing, and listening here in 2013.

Some scraps from the unpublished posts of 2012.

Open City, Teju Cole (2011) I’ve wondered what an American Sebald would sound like. Cole provides a useful and provocative redirection for the question. The ways Cole thinks through history, space, literature, memory, and tone are consistently provocative, but as in Sebald, the overall impression remains one of stillness. A deceptively simple novel. I want to read it again in a year.

I wanted to like HHhH more than I did; it seemed unnervingly slight, too playful. I enjoyed Martha Marcy May Marlene, which was amateurish but affecting. I had to switch off a number of movies for intolerable violence, including Savages and Lawless. This is unusual for me; either the violence is getting worse or I’m getting less tolerant or both. In Moonrise Kingdom I saw Wes Anderson beginning to imitate himself and it made me sad. Cronenberg’s Freud movie was stupid; I don’t think Cronenberg has one single thing left to say and as such his attachment to Delillo’s Cosmopolis makes a great deal of sense. Almovodar’s The Skin I Live In was awesome and irresistible. That one I could go on about. The superficial level of the film being “about” identity politics — you could certainly lead a rousing discussion about the performance of gender in the film with a room full of students — but what really fascinates me is its crazy structure and pacing, like a 19th century generational novel crossed with TMZ.

Plus a bunch of other stuff I’m sure, but like I said, in 2012 I mostly spent my spare time watching photography how-to videos on YouTube and wondering if I’d ever write another word. I’m going to try to keep up this year. I’ll also post some photos from time to time, I think.