Grant’s an itinerant English writer who got beguiled by the memory, amnesia, beauty, and ugliness of the Mississippi Delta region and wound up buying a house and spending enough time there to develop some relationships with people and a better-than-facile understanding of the place, its culture, history, and inhabitants. I would hope any undergrad fresh from Anthropology 101 could shoot this book full of holes easy as shotgunning a speed limit sign outside Itta Bena. Grant is white, educated, urbane, and for God’s sake British; we can easily question both his capacity to understand and his right to speak. To his credit, he cops to all that, not in a self-flagellating way but with amiable candor. Some will surely say he is too quick to grant himself permission and authority. I found myself trusting him. No, that’s not quite true; I don’t trust him, but he’s resolutely well-intentioned and a seductive storyteller, so I was willing to bracket my resistance for a spell and enjoy his anecdotes. It helps that he’s resolutely in the mode of first person memoir with occasional gestures toward cultural analysis. The claims are less “here’s how things are” than “given my experience, this is what I think might be so.” (Geoff Dyer’s The Missing of the Somme, which my next post will be about, inverts this pattern.)

Grant’s an itinerant English writer who got beguiled by the memory, amnesia, beauty, and ugliness of the Mississippi Delta region and wound up buying a house and spending enough time there to develop some relationships with people and a better-than-facile understanding of the place, its culture, history, and inhabitants. I would hope any undergrad fresh from Anthropology 101 could shoot this book full of holes easy as shotgunning a speed limit sign outside Itta Bena. Grant is white, educated, urbane, and for God’s sake British; we can easily question both his capacity to understand and his right to speak. To his credit, he cops to all that, not in a self-flagellating way but with amiable candor. Some will surely say he is too quick to grant himself permission and authority. I found myself trusting him. No, that’s not quite true; I don’t trust him, but he’s resolutely well-intentioned and a seductive storyteller, so I was willing to bracket my resistance for a spell and enjoy his anecdotes. It helps that he’s resolutely in the mode of first person memoir with occasional gestures toward cultural analysis. The claims are less “here’s how things are” than “given my experience, this is what I think might be so.” (Geoff Dyer’s The Missing of the Somme, which my next post will be about, inverts this pattern.)

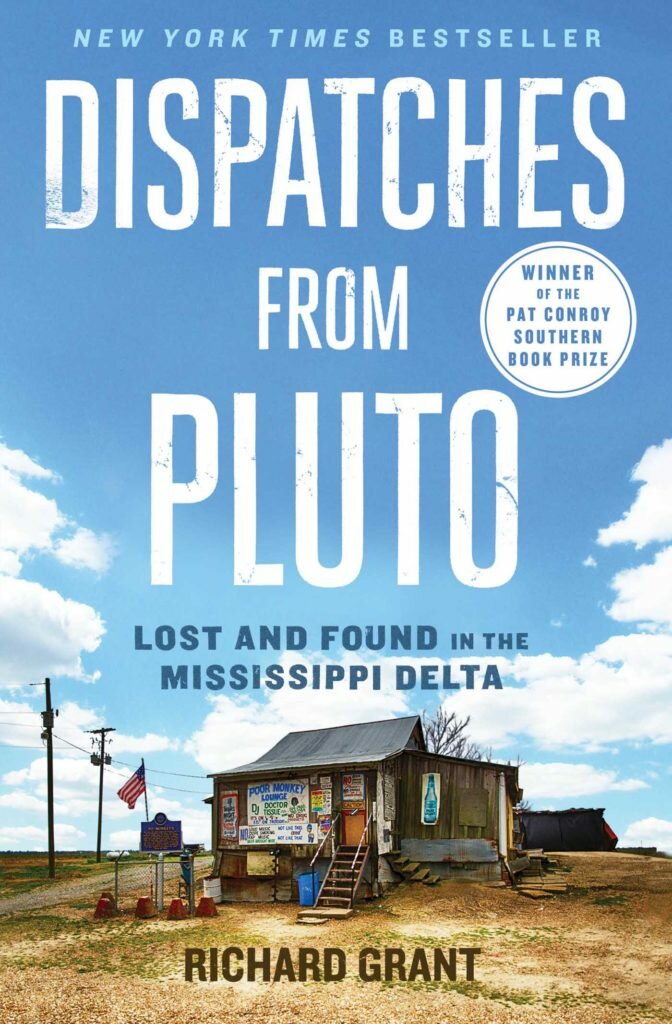

I’ve spent some time in the Delta as a tourist, and every time I go I feel a little more confused about why I’m there. Like other tourists, I went the first time because it’s where American music was born. I also wanted to see the cotton fields I’d only imagined, and to put my hand on the rails that carried the Great Migration from Greenwood to Memphis to Cairo to Chicago. Given its history, the Delta is arguably the most American place there is. But sadly, being the most American place there is also means it is a place of enduring inequality, injustice, poverty, and utter resistance to change. The Delta loves to “celebrate heritage” with museums, memorials, cultural centers, ersatz juke joints, roadside markers, and the like. In recent decades, some of these gestures — the Emmett Till Center in Glendora, for example — have done much to bring attention to the evil which runs through that heritage like arteries through a body. But I think many visitors, myself and Richard Grant included, are too easily tempted to turn from the evil and focus on the charm, or what appears to be charm. A simple thought experiment: If Grant were everything he is — British, educated, urbane, gregarious, etc. — and also black, how would his reception in the Delta been different?